The Myth of Gold Parity

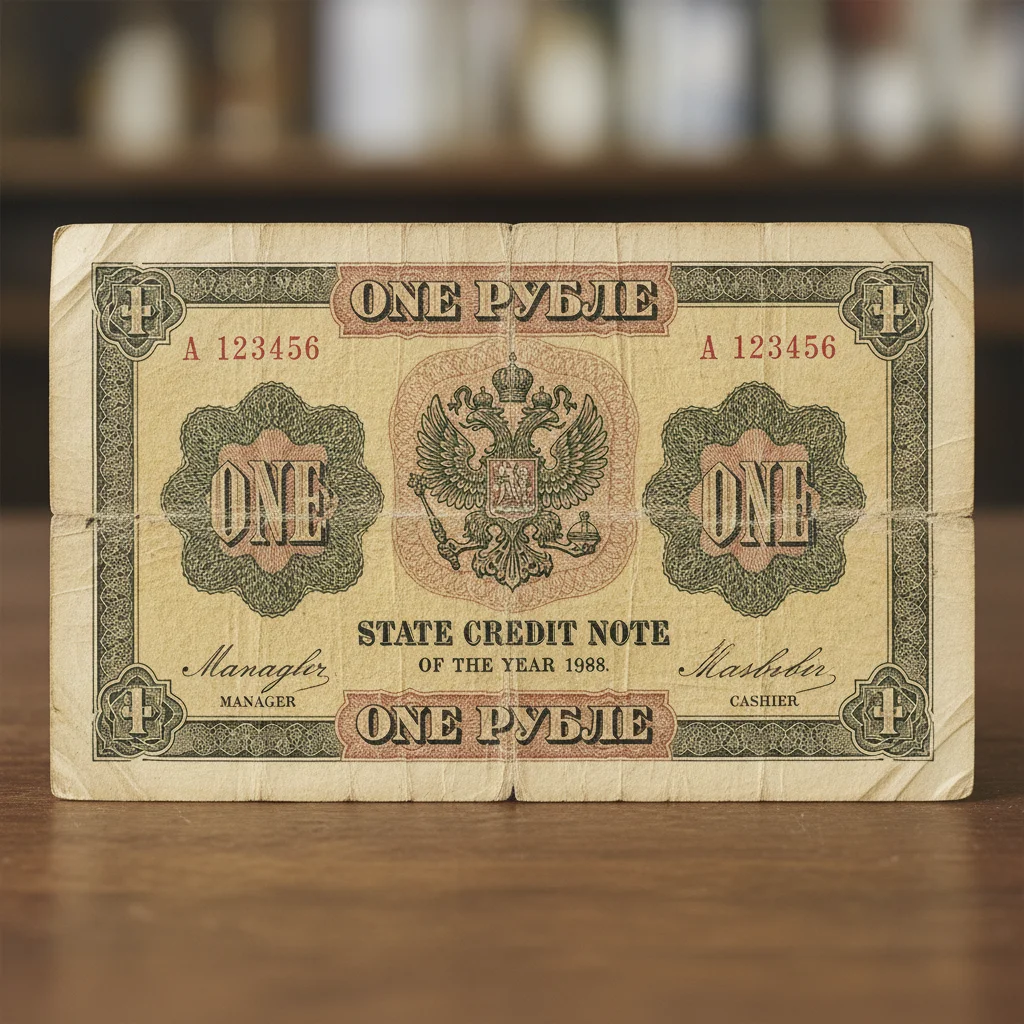

One of the common myths is the idea of the extremely high purchasing power of the pre-revolutionary ruble. This myth, actively promoted since the late 1980s, is based on recalculating the ruble's value through its gold content.

From January 3, 1897, the gold content of the ruble was set at 0.77423544 grams. If this value is multiplied by the modern price of gold (for example, 4360.1 rubles per gram), it would seem that one Tsarist ruble is equivalent to 3375.74 modern Russian rubles.

This calculation method is incorrect and creates a distorted view of the real value of money in the past. It does not take into account the price structure, wage levels, or the availability of goods at that time.

Wages in Tsarist Russia Converted to Gold

Applying the gold parity method to pre-revolutionary wages leads to fantastic figures. For example, the average salary of a worker in 1913 was 23 rubles and 50 kopecks. Converted through gold, this is equivalent to almost 79,330 modern rubles.

An even more impressive result is obtained when analyzing an officer's salary. A captain commanding an infantry company in his first four years of service received 135 rubles a month. Recalculating this amount based on gold parity yields an incredible 455,725 rubles, which is about seven times higher than the salary of a modern captain in a similar position (around 65,000 rubles).

These examples clearly demonstrate why recalculating through the value of gold is erroneous and does not reflect real purchasing power.

The True Calculation Method: Purchasing Power Parity

To correctly determine the value of the pre-revolutionary ruble, the purchasing power parity (PPP) method should be used. It involves comparing the prices of a wide range of goods and services across different historical periods.

To obtain an objective result, one must take all known past prices, compare them with modern prices for similar goods, and then sum the differences and divide by the number of items compared. The more goods and services involved in the comparison, the more accurate the final parity will be.

Despite the fact that many goods and services have disappeared or appeared over time, the lists of goods from the pre-revolutionary and modern periods overlap by about 76%. This is sufficient to conduct a reasonably accurate and objective analysis.

The Problem of 'Mono-Indicators'

| Product | Price Difference |

| Potatoes | 2147 times |

| Granulated sugar | 174 times |

| Vodka | 1000 times |

| Bread | 226 times |

Attempting to calculate parity based on a single product, or a 'mono-indicator', leads to completely different and subjective results. This is because prices for different groups of goods have changed unevenly.

A comparison of prices for individual products between 1913 and 2021 yields the following results:

Such a wide range of values shows that using a single product to compare purchasing power is incorrect. Furthermore, the structure of consumption must also be taken into account. For example, before the revolution, four times more black bread was eaten than white bread, whereas today the situation is the opposite.

The Fall of the Ruble: From the Gold Standard to War Communism

The real purchasing power of the ruble began to fall long before the revolution. Taking the 1913 level as 100%, one can trace the rapid depreciation of money in the following years.

Dynamics of the decline in the ruble's purchasing power relative to 1913:

- 1897 — 167%

- 1913 — 100%

- March 1917 — 24%

- October 1917 — 15%

- May 1918 — 9%

- November 1918 — 4%

- December 1918 — 3.2%

By the time of the 1924 monetary reform, hyperinflation had reached colossal proportions. One new ruble with the former gold content was exchanged for 50 thousand 1923-issue rubles or 50 billion 1921-issue rubles.

The Soviet Ruble: From the NEP to Post-War Deflation

The restoration of the gold standard in 1924 did not return prices to the pre-revolutionary level. The purchasing power of the new Soviet ruble was only 62.5% of the 1913 ruble. For example, a bottle of vodka now cost 1 ruble instead of 40 kopecks, and a dozen eggs cost 60 kopecks instead of 32.

In the following years, the ruble continued to weaken. By 1927, its purchasing power had fallen to 55% of the 1913 level, by 1929 to 48%, and by 1937 to a catastrophic 5.85%. What cost 1 ruble in 1913 now cost 17 rubles in 1937.

After the 1947 monetary reform, the parity of the Tsarist ruble to the Soviet one was 1 to 61.28. However, from 1948, a policy of systematic price reduction began, and by 1951, the Tsarist ruble was equivalent to 34.31 Soviet rubles. The peak of deflation occurred in 1953, when this ratio reached 1 to 27.14.

Khrushchev's Reform and the Birth of Scarcity

After 1954, when the April price reduction was the last, inflationary processes resumed in the USSR economy. By 1960, the parity of the Tsarist ruble to the Soviet one was 1 to 28.32.

The 1961 monetary reform changed the situation again. After the redenomination, 1 Tsarist ruble became worth 3 rubles and 11 kopecks in new Soviet money. However, inflation did not stop, and by the end of 1962, its value had risen to 3 rubles and 31 kopecks.

The main consequence of the reform was that an increasing range of goods began to fall into the category of deficit. Products disappeared from state trade but appeared on the black market, where prices were formed according to different, speculative laws.